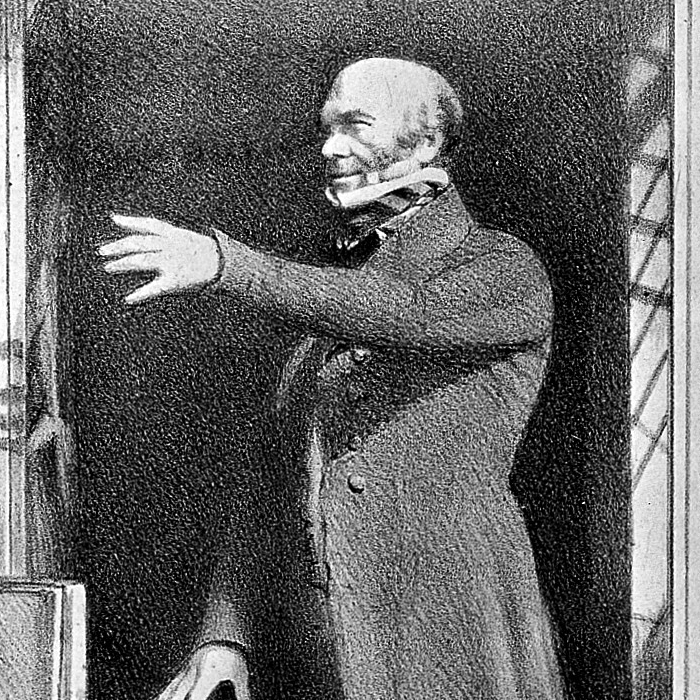

Robert Knox

Robert Knox shared with Charles Hamilton Smith a record of service in the Napoleonic Wars (Knox as a surgeon) and a fascination, amounting in Knox’s case to an obsession, with the subject of race. Knox’s treatise, The Races of Men, was, like Smith’s Natural History of the Human Species, an attempt to define race as an object of science. Unlike Smith, however, Knox insisted on the primacy of a single scientific approach, a fully biologized concept of race premised on the organizational scheme of nature. Climate, ways of life, even history were for him facts of secondary importance.

Undistinguished as an original thinker, Knox was highly responsive to intellectual currents, including the gradual shift in meaning by which the term race, once a name for essentialized human groups, had become over the preceding years an abstract noun. In a sentence that became famous as the purest expression of extreme racial determinism as well as a sign of the dramatic emergence in recent European discourse of the race concept, Knox said that “race is everything: literature, science, art, in a word civilization, depend on it” (7).

Knox’s insistence on biological determinism (as opposed, for example, to Prichard’s historical approach) did not prevent him from including in his lectures a number of environmentalist and other arguments that were circulating at mid-century. Whereas Blumenbach had excluded everything non-physical in his approach, Knox introduced considerations of customs, behavior, and history as evidence of racial characters. His lectures—rapid, diffuse, irritable, brittle, repetitive, sometimes belligerent—ranged widely over a huge range of subjects including the history of the earth, comparative civilizations, the movement of the heavenly orbs, the stages of fetal development, the merits of certain philosophical theories, and the relative beauty of women of various races. But race was his constant preoccupation, and served as an explanatory principle for many otherwise complex events. The 1848 revolutions in Europe were, for Knox, the consequence of irreconcilable racial differences on the crowded European continent, as were other conflicts that seemed to those not attuned to deeper truths to be political, economic, or cultural in origin. As one scholar put it, Knox promoted “a racial fantasy in which Saxons, Celts, gypsies, Slavonians, Caffres, Copts, Bohemians, Sarmatians, Jews, and the dark races of the world played out their biological destinies.”*

Knox was equivocally both monogenetic and polygenetic in his understanding of race. Citing Cuvier, whom he had met in Paris in 1821, and Geoffroy St.-Hilaire, Knox acknowledged that in the never-to-be-restored beginning, humanity was “one family” with “one origin” (297). At some point, through a process about which we can only speculate, Knox said, races were formed and distributed throughout the world, their natural endowments consolidating through heredity to the point where each race now constituted a distinct group with “its own form of civilization, as it has its own language and arts; I would almost venture to say, science” (46). These forms were not, for Knox, either temporary or equal in value. “Specific characters in the quality of the brain itself” had produced a hierarchy that had become natural in which Anglo-Saxons were in the lead and “the dark races of men,” burdened by a “psychological inferiority,” lagged behind.

Knox is often linked with candidly racist ideologues such as Gobineau, Houston Stewart Chamberlain, Lothrop Stoddard, and others who ranked the races of the world, invariably placing Caucasians in the lead and Negroes at or near the end. The Races of Men opens with a long discourse on the Anglo-Saxon race, which Knox regarded as the rightfully dominant race in the world. But Knox fits uneasily in such company for several reasons. First, he did not believe in what he called the “Caucasian dream” of Blumenbach and Prichard, which assimilated many races—Saxons, Franks, Celts, etc.—into a phantasmatic unity (60). Nor, unlike Charles Hamilton Smith, did he believe that the European races were either entirely virtuous or unambiguously admirable, or that the dark races were, their limitations notwithstanding, altogether savage. Indeed, he identified the Celts as “the source of all evil”—a viewed largely shared by Meiners, Darwin, Haeckel, Pinkerton, and Gobineau, but dismissed with extreme prejudice by Renan. Most significantly, Knox was strongly opposed to the use of race and racial difference to justify domination, colonial exploitation, or imperial adventures. Having served in South Africa, Knox had seen, and had condemned, the Boers’ contempt for indigenous peoples. In his view, a principle of natural separation dictated that each race should be left unmolested in the environment in which it could best flourish, with none permitted to dominate any others.

On the same principle, Knox opposed all forms of racial mixing, not because he felt that racial integrity, especially of the higher or more advanced race, should be preserved from any possibility of dilution or pollution but because mixture ran against the tendency of nature to reject anomalies and revert to pure strains, which were the hardiest and had the best chance of survival—agreeing in this respect with Long but differing from Buffon and Virey, who felt that hybrids were often more vigorous. Hybrids or mulattos throughout the organic world, Knox argued, possessed diminished vitality and could not reproduce themselves for long, a view he shared with Charles Hamilton Smith.

On the other hand, Knox understood that the iron law of nature dictated that nothing lasted forever, and that organic life had been produced in such “extravagant and unintelligible abundance” that there were no pure races left. This meant that the racial traits he described with such precision and assurance were products of inference rather than observation, but for Knox the more important conclusion was that all races were doomed to extinction. Between periodic racial slaughters and the chaotic course of history itself, races were “destined to run, like all other animals, a certain limited course of existence” (308). Indeed, Knox prophesied that, at least in the tropics, the energetic Negro would likely supersede the “fair races” (see Appendix).

One striking feature of Knox’s naturalism was a proto-Darwinian suggestion that as the apex of creation, man actually recapitulated, during the process of fetal development, all the lower species. Such a theory, present in rudimentary form in the work of Charles Hamilton Smith, would be developed by Haeckel under the slogan “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny.”

If, as George W. Stocking, Jr. has said, British racial science was “Prichardian” until Prichard’s death in 1848, it became more polygenetic, anti-environmentalist, and biological thereafter. Knox’s work played a significant role in that shift, and in the development of the discipline of anthropology.** James Hunt, founder of the Anthropological Society of London, had been Knox’s secretary at the Ethnological Society. But during his lifetime and for many years thereafter, Knox’s reputation did not rest solely or even primarily on his scientific work. Twenty years before he published The Races of Men he became infamous for his involvement in a grisly scheme discovered in 1829 by which bodies were obtained for dissection and medical research through the serial murder of poor people. Knox, who performed research on the cadavers, had never dealt directly with the killers, and was not charged—although he was burnt in effigy.

*Nancy Stepan, The Idea of Race in Science (London: Macmillan, 1982), 41.

**George W. Stocking, Jr., “What’s in a Name? The Origins of the Royal Anthropological Institute (1837-1871),” Man 6 (1971): 369-90.

The Races of Men: A Fragment

Introduction

The basis of the view I take of man is his Physical structure; if I may so say, his Zoological history. To know this must be the first step in all inquiries into man’s history: all abstractions, neglecting or despising this great element, the physical character and constitution of man, his mental and corporeal attributes must, of necessity, be at the least Utopian, if not erroneous. Men are of various Races; call them Species, if you will; call them permanent Varieties; it matters not. The fact, the simple fact, remains just as it was: men are of different races. Now, the object of these lectures is to show that in human history race is everything. (9-10)

I, in opposition to these views, am prepared to assert that race is everything in human history; that the races of men are not the result of accident; that they are not convertible into each other by any contrivance whatever. The eternal laws of nature must prevail over protocols and dynasties: fraud,—that is, the law; and brute force—that is, the bayonet, may effect much; have effected much; but they cannot alter nature. . . . We know not the history of any one race on the earth. All is conjecture, pretension, error, obscurity. The most illustrious name applied to any race has been the Roman, and yet it does not appear that there ever was any distinct race to which this name could be applied! (14-15)

To be brief, and so conclude.—What is race, and what is species? These terms are easier understood than defined. That the idea of distinct species and of race is fast passing away from the human mind, may, or may not be true; the old doctrine has been deeply shaken; still species and race exist for us; for man, at least; in space, though not in time. In time there is probably no such thing as species: no absolutely new creations ever took place. . . . Of one thing we are certain, entire races of animals have disappeared from the surface of the globe; other seemingly new creations occupy their place. But is it really a new creation? This question we shall also discuss.

Look more narrowly into the races of men, and you will find them to be subject to diseases peculiar to each; that the very essence of their language is distinct; their civilization also, if they have any. (34)

Lecture I. History of the Saxon or Scandinavian Race

When the word race, as applied to man, is spoken of, the English mind wanders immediately to distant countries; to Negroes and Hottentots, Red Indians and savages. He admits that there are people who differ a good deal from us, but not in Europe; there mankind are clearly of one family. It is the Caucasian race, says one; it is the primitive race, says another. But the object of this work is to show that the European races, so called, differ from each other as widely as the Negro does from the Bushman; the Caffre from the Hottentot; the Red Indian of America from the Esquimaux; the Esquimaux from the Basque. Blumenbach and Prichard have misled the public mind so much in this respect, that a century may elapse before it be disabused. (39)

Climate has no influence in permanently altering the varieties or races of men; destroy them as it may and does, but it cannot convert them into any other race. . . .

Thoughtful, plodding, industrious beyond all other races, a lover of labour for labour’s sake; [the Saxon] cares not its amount if it be but profitable; large handed, mechanical, a lover of order, of punctuality in business, of neatness and cleanliness. In these qualities no race approaches him; the wealthy with him is the sole respectable, the respectable the sole good; the word comfort is never out of his mouth—it is the beau ideal of the Saxon.

His genius is wholly applicative, for he invents nothing. In the fine arts, and in music, taste cannot go lower. The race in general has no musical ear, and they mistake noise for music. The marrow-bones and cleaver belong to them. Prize fights, bull-baiting with dogs; sparring matches; rowing, horse racing, gymnastics: the Boor is peculiar to the Saxon race. When young they cannot sit still an instant, so powerful is the desire for work, labour, excitement, muscular exertion. The self-esteem is so great, the self-confidence so matchless, that they cannot possibly imagine any man or set of men to be superior to themselves. Accumulative beyond all others, the wealth of the world collects in their hands. (44-45)

No race perhaps—(for I must make allowances for my Saxon descent,)—no race perhaps exceeds them in an abstract sense of justice, and a love of fair play; but only to Saxons. This of course they do not extend to other races. Aware of his strength of chest and arms, he uses them in self-defence: the Celt flies uniformly to the sword. To-day and to-morrow is all the Saxon looks to; yesterday he cares not for; it is past and gone. He is the man of circumstances, of expediency without method; “try all things, but do not theorize.” Give me “constants,” a book of constants; this is his cry. Hence his contempt for men of science: his hatred for genius arises from another cause; he cannot endure the idea that any man is really superior in anything to himself. The absence of genius in his race he feels; he dislikes to be told it: he attempts to crush it wherever it appears. Men of genius he calls humbugs, impostors. (47)

Physiological Question

Section I—Do races ever amalgamate? What are the obstacles to a race changing its original locality?

I have heard persons assert, a few years ago, men of education too, and of observation, that the amalgamation of races into a third or new product, partaking of the qualities of the two primitive ones from which they sprung, was not only possible, but that it was the best mode of improving the breed. The whole of this theory has turned out to be false:—1st. As regards the lower animals; 2d. As regards man. Of the first I shall say but little: man is the great object of human research; the philosophy of Zoology is not indeed wrapt up in him; he is not the end, neither was he the beginning: still, as he is, a knowledge of man is to him all-important.

The theories put forth from time to time, of the production of a new variety, permanent and self-supporting, independent of any draughts or supplies from the pure breeds, have been distinctly disproved. It holds neither in sheep nor cattle: and an author, whose name I cannot recollect, has refuted the whole theory as to the pheasant and to the domestic fowl. He has shown that the artificial breeds so produced are never self-supporting. Man can create nothing: no new species have appeared, apparently, for some thousand years; but this is another question I mean not to discuss here, although it is obvious that if a hybrid could be produced, self-supporting, the elaborate works of Cuvier would fall to the ground. The theory of Aristotle, who explained the variety and strangeness of the animal forms in Africa, on the grounds that a scarcity of water brought to the wells and springs animals of various kinds, from whose intercourse sprung the singularly varied African Zoology, has been long known to be a mere fable.

Nature produces no mules; no hybrids, neither in man nor animals. When they accidentally appear they soon cease to be, for they are either non-productive, or one or other of the pure breeds speedily predominates, and the weaker disappears. This weakness may either be numerical or innate.

That this law applies strictly to man himself, all history proves: I once said to a gentleman born in Mexico,—Who are the Mexicans? I put the same question to a gentleman from Peru, as I had done before to persons calling themselves Germans—neither could give a distinct reply to the question. The fact turns out to be, that there really are no such persons; no such race. (51-53)

Lecture II. Physiological Laws Regulating Human Life

How are the races of men produced? whence come they? whither tend they? Already a learned divine has stretched the link between the 2d and 3d verses of the Mosaic record to a coil so extended, so elastic, as to leave on the part of the scientific nothing to desire; and whilst I write this passage, a friend has pointed out to me that a learned theologian, if not an orthodox divine, who writes on a subject of which I fear he does not know much, —“the Unity of Man” —cautions his readers not to mistake the chronology of Bishop Usher for the true chronology of man, which he candidly admits has never yet been discovered: he prepares his readers for a lengthening of the period to account for the different races! I knew it must come to this—another version of the Mosaic record to the hundreds already existing. For the present, I leave the chronological part in their hands, proceeding with the inquiry into the physiological laws regulating human life.

That by mere climate, giving to the expression its utmost range of meaning, a new race of men can be established in perpetuity, is an assertion which for the present is contradicted by every well-ascertained physiological law, and by all authentic history. On the limited habitable territory of the Cape of Good Hope, shut in by deserts and by the sea, lived, when the Saxon Hollander first landed there, two races of men, as distinct from each other as can be well imagined, the Hottentot, or Bosjeman, and the Amakoso Caffre. To these was added a third, the Saxon Hollander. What time the Bosjeman child of the desert had hunted these desert and arid regions, for what period the Hottentot had listlessly tended his flocks of fat-tailed sheep, how long the bold Caffre had herded his droves of cattle, cannot now be ascertained: the Saxon Hollander found them there 300 years ago, as they are now in respect of physical structure and mental qualifications, inferior races, whom he drove before him, exterminating and enslaving the coloured man; destroying mercilessly the wilde which nature had placed there; and with the wilde, ultimately the coloured man, in harmony with all around him—antagonistic, it is true, but still in harmony to a certain extent; non-progressive; races which mysteriously had run their course, reaching the time appointed for their destruction.

To assert that a race like the Bosjeman, marked by so many peculiarities, is convertible, by any process, into an Amakoso Caffre or Saxon Hollander, is at once to set all physical science at defiance. If by time, I ask what time? The influence of this element I mean to refute presently: the Dutch families who settled in Southern Africa three hundred years ago, are now as fair, and as pure in Saxon blood, as the native Hollander; the slightest change in structure or colour can at once be traced to intermarriage. By intermarriage an individual is produced, intermediate generally, and partaking of each parent; but this mullato man or woman is a monstrosity of nature—there is no place for such a family: no such race exists on the earth, how ever closely affiliated the parents may be. . . .

This seems to be the law. By intermarriage a new product arises, which cannot stand its ground; 1st. By reason of the innate dislike of race to race, preventing a renewal of such intermarriages; 2d. Because the descendants will of necessity fall back upon the stronger race, and all traces, or nearly so, of the weaker race must in time be obliterated. (64-67)

Lecture VI. The Dark Races of Men

. . . to me the unity of man appears evident; but if so, whence come the dark races? and why is it that destiny seems to have marked them for destruction? . . . Did we know the law which originated the coloured races we should be able, no doubt, to foretel their future destiny. Whether doomed to destruction and extermination before the savage energy of the Saxon and Celt, the Russ and Slavonian, or protected by the unconquerable forest —the tropical forest; by the desert; by the jungle and fen, the bog and marsh; by the all-powerful tropical sun and snow-clad icy barriers of the arctic circle; or withering and so—perishing before the as yet undiscovered laws of population, which unseen extinguishes the hopes of races and of nations, Mongol and Copt, American and Saxon, yet they may stand their ground during the present order of the material world, feebly contending against the stronger races for a corner of that earth, which we have been told was given to man as an inheritance. Did we know the law of their origin we should know the law of their extinction; but this we do not know. All is conjecture, uncertainty. (147-48)

From the earliest recorded times might has always constituted right, or been held to do so. By this right the Slavonic race crushes down Italy, withering and blasting the grandest section of mankind. By this kind of right, that is, power or might, we seized on North America, dis possessing the native races, to whom America naturally be longed; we drove them back into their primitive forests, slaughtering them piteously; our descendants, the United States men, drove us out by the same right, that is, might. The same tragedy was repeated in South America; the mingled host of Celtiberian adventurers brought against the feeble Mexican, Peruvian, and Brazilian, the strength and knowledge and arms of European men; the strength of a fair or, at least, of a fairer race. The Popes of Rome sanctified the atrocities; it was the old tragedy again, the fair races of men against the dark races; the strong against the feeble; the united against those who knew not how to place even a sentinel; the progressists against those who stood still—who could not or would not progress. Look all over the globe, it is always the same; the dark races stand still, the fair progress. . . .

Since the earliest times, then, the dark races have been the slaves of their fairer brethren. Now, how is this? Mr. Gibbon solves the question in his usual dogmatic way; he speaks of the obvious physical inferiority of the Negro; he means, no doubt, the dark races generally, for the remark applies to all. But, notwithstanding the contrary opinion professed by Dr. Tiedemann respecting the great size of some African skulls, which he found in my own museum, sent to me from the western coast of Africa, I feel disposed to think that there must be a physical and, consequently, a psychological inferiority in the dark races generally. This may not depend altogether on deficiency in the size of the brain en masse, nor on any partial defects; to which, however, I shall advert presently; but rather, perhaps, to specific characters in the quality of the brain itself. It may, perhaps, be right to consider first the different obvious physical qualities of the dark races, before we enter on the history of their position as regards the mass of mankind, and especially as regards those races which seem destined, if not to destroy them altogether, at least to limit their position to those regions of the earth where the fair races can neither labour nor live—the equatorial regions and the regions adjoining the tropics, usually termed by romancists and travellers, and not unfairly, the grave of Europeans.

First, as regards mere physical strength, the dark races are generally much inferior to the Saxon and Celt; the bracelets worn by the Kaffirs, when placed on our own arms, prove this. Secondly, in size of brain they seem also considerably inferior to the above races, and no doubt also to the Sarmatian and the Slavonic. Thirdly, the form of the skull differs from ours, and is placed differently on the neck; the texture of the brain is I think generally darker, and the white part more strongly fibrous; but I speak from extremely limited experience. Mr. Tiedemann, I think it is, who says that the convolutions of the upper surface of the two hemispheres of the brain are nearly symmetrical; in our brain the reverse always happens. Lastly, the whole shape of the skeleton differs from ours, and so also I find do the forms of almost every muscle of the body. (148-152)

But who are the dark races of ancient and modern times? It would not be easy to answer this question. Were the Copts a dark race? Are the Jews a dark race? The Gipsies? The Chinese, &c? Dark they are to a certain extent; so are all the Mongol tribes—the American, Indian and Esquimaux—the inhabitants of nearly all Africa—of the East—of Australia. What a field of extermination lies before the Saxon Celtic and Sarmatian races! The Saxon will not mingle with any dark race, nor will he allow him to hold an acre of land in the country occupied by him; this, at least, is the law of Anglo-Saxon America. The fate, then, of the Mexicans, Peruvians, and Chilians, is in no shape doubtful. Extinction of the race—sure extinction—it is not even denied. (153)

The Caffres are closely allied to the Negro race, and probably graduate, as it were, into them; for, as Nature has formed many races of white men whose physical organization and mental disposition differ widely from each other, so also has she formed the swarthy world. It is not necessary, neither perhaps, is it at all correct, to call a Caffre a Negro, or a Negro a Caffre; neither are the Caffres degenerated Bedouins, nor well-fed Hottentots, nor Saxons turned black by the sun, nor Arabs, nor Carthaginians. I would as soon say they were the ten lost tribes. All these theories are on a par, and are worthy of each other, but not worthy of any notice. Their language is soft and melodious, and they seem to have an ear for simple melody. Since I first saw them in 1817 they have acquired firearms and horses; but they want discipline—the firmness of discipline. Individual acts of bravery they have often performed, but combined they can never meet successfully the European. We are now preparing to take possession of their country, and this of course leads to their enslavery and final destruction, for a people without land are most certainly mere bondmen. . . . What travellers and others tell you about tribes of mixed breed, races of mulattoes, has no real existence; I would as soon expect to hear of a generation of mules. When the Negro is crossed with the Hottentot race, the product is a mild-tempered, industrious person; when with the white race, the result is a scroundrel [sic]. But, cross as you will, the mulatto cannot hold his ground as a mulatto: back the breed will go to one or other of the pure breeds, white or black. I have already explained all this.

And now for the Negro and Negroland—Central Africa, as yet untrodden and unknown. Look at the Negro, so well known to you, and say, need I describe him? Is he shaped like any white person? Is the anatomy of his frame, of his muscles, or organs like ours? Does he walk like us, think like us, act like us? Not in the least. What an innate hatred the Saxon has for him, and how I have laughed at the mock philanthropy of England! But I have spoken of this already, and it is a painful topic; and yet this despised race drove the warlike French from St. Domingo, and the issue of a struggle with them in Jamaica might be doubtful. But come it will, and then the courage of the Negro will be tried against England. Already they defeated France; but, after all, was it not the climate? for that any body of dark men in this world will ever fight successfully a French army of twenty thousand men I never shall believe. With one thousand white men all the blacks of St. Domingo could be defeated in a single action. This is my opinion of the dark races. . . .

The past history of the Negro, of the Caffre, of the Hottentot, and of the Bosjeman, is simply a blank—St. Domingo forming but an episode. Can the black races become civilized? I should say not; their future history, then, must resemble the past. The Saxon race will never tolerate them—never amalgamate—never be at peace. The hottest actual war ever carried on—the bloodiest of Napoleon’s campaigns—is not equal to that now waging between our descendants in America and the dark races; it is a war of extermination — inscribed on each banner is a death’s head and no surrender; one or other must fall. But here climate steps in, and says to the land-grasping Saxon, “I give you a choice of evils — cultivate Central Africa or Central America with your own hands, and you perish; employ the coloured man, your brother, as a slave, and live under the continual fear of his terrible vengeance—terrible when it comes, as come it will: unrelenting, merciless.” A million of slave-holders cut off in cold blood to-morrow would call forth no tear of sympathy in Europe: “Bravo !” we should say; “the slave has risen and burst his chains — he deserves to be free.” (160-63)

Lecture VII. History of the Celtic Race

Each race has its own ideas of liberty. There is but one race whose ideas on this point are sound; that race is the Saxon. He is the only real democrat on the earth, who combines obedience to the law with liberty. But the law must be made by himself, and not forced on him by another; hence the successive revolutions in England to overturn the Norman law and the Norman government; hence the struggle now approaching, which will not be the last. (250)

Lecture VII. History of the Celtic Race

. . . the source of all evil lies in the race, the Celtic race of Ireland. There is no getting over historical facts. Look at Wales, look at Caledonia; it is ever the same. The race must be forced from the soil; by fair means, if possible; still they must leave. England’s safety requires it. I speak not of the justice of the cause; nations must ever act as Machiavelli advised: look to yourself. The Orange club of Ireland is a Saxon confederation for the clearing the land of all papists and jacobites; this means Celts. If left to themselves, they would clear them out, as Cromwell proposed, by the sword; it would not require six weeks to accomplish the work. But the Encumbered Estates Relief Bill will do it better. (253-54)

Concluding Lecture

Let us now briefly review the progress we have made in this the highest of all analyses: deepest of all theories: most important to man. Man, we have seen, stands not alone, he is one of many; a part and parcel of the organic world, from all eternity. That organic world is the product of secondary causes. During his growth he undergoes numerous metamorphoses, too numerous even for the human imagination. These have a relation to the organic world. They embrace the entire range of organic life, from the beginning to the end of time. Nature can have no double systems; no amendments or second thoughts; no exceptional laws. Eternal and unchanging, the orbs move in their spheres precisely as they did millions of years ago. Proceeding, as it were, from an invisible point endowed with life, he passes rapidly, at first, through many forms, all resembling, more or less, either different races of men from his own, or animals lower in the scale of being; or beings which do not now exist, though they probably once did, or may at some future time. When his development is imperfect, it represents then some form, resembling the inferior races of men, or animals still lower in the scale of being. Moreover, what is irregular in him is the regular structure in some other class of animals. Take for example the webbed hand or foot occasionally found in man, constant in certain animals, —as in the Otter and Beaver; constant also in the human fœtus, that is, the child before birth. Take for example the cuticular fold at the inner angle of the eye, so common with the Esquimaux and Bosjeman or Hottentot (the corresponding yellow races of the northern and southern hemispheres), so rare in the European, but existing in every fœtus of every race. Nor let it be forgotten that forms exist in the human foetus which have nothing human in them in the strictest sense of the term; that the fœtus of the Negro, does not, as has been stated, resemble the fœtus of the European, but that the latter resembles the former, all the more resembling the nearer they are to the embryonic condition. Unity of structure, unity of organization, unity of life, at the commencement of time, whether measured by the organic world or by the duration of individual life. (288-89)

“There is but one animal," said Geoffroy [St.-Hilaire],” not many;" and to this vast and philosophic view, the mind of Cuvier himself, towards the close of life, gradually approached. It is, no doubt, the correct one. Applied to man, the doc trine amounts to this,—Mankind is of one family, one origin. In every embryo is the type of all the races of men; the circumstances determining these various races of men, as they now, and have existed, are as yet unknown; but they exist, no doubt, and must be physical; regulated by condary [probably secondary] laws, no changing, slowly or suddenly, the existing order of things. The idea of new creations, or of any creation saving that of living matter is wholly inadmissible. The world is composed of matter, not of mind. The circumstances giving rise, then, to the specializations of animal and vegetable forms, giving them a permanency of some thousand years, are as yet unknown to us, and may for ever remain so; but that is no reason why they should not be inquired into. . . .

In conclusion: the permanent varieties of men, permanent at least seemingly during the historic period, originate in laws elucidated in part by embryology, by the laws of unity of the organization, in a word, by the great laws of transcendental anatomy. Variety is deformity; deviation from one grand type towards which Nature, by her laws of specialization, constantly aims: those laws which, once established, terminated the reign of chaos. To every living thing they give a specific character, enduring at least for a time; man also has his specific character to endure for a time. Certain forms, certain deviations, in obedience to the great and universal law of unity, are not viable in the existing order of things; but they may become so. If the deformity, that is, a return more or less to unity, be too great, too antagonistic of her specific laws, the individual, whether man or mere animal or plant, ceases to be, and thus the extension of variety of forms, which we call “deformations,” ceases. (297-98)

Section I.—Origin, Civilization, Extinction of the Dark Races of Men

If there be a dark race destined to contend with the fair races of men for a portion of the earth, given to man as an inheritance, it is the Negro. The tropical regions of the earth seem peculiarly to belong to him; his energy is considerable: aided by a tropical sun, he repels the white invader. From St. Domingo he drove out the Celt; from Jamaica he will expel the Saxon; and the expulsion of the Lusitanian from Brazil, by the Negro, is merely an affair of time. (306)

Michael D. Biddiss, “The Politics of Anatomy: Dr Robert Knox and Victorian Racism,” Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 69 (1976), 245-50.

Robert Knox, The Races of Men: A Philosophical Enquiry into the Influence of Race over the Destinies of Nations (London: Forgotten Books, 2017) (enlarged version of The Races of Men, 1862).

Kathy Alexis Psomiades, “Polygenist Ecosystems: Robert Knox’s The Races of Men (1850),” Victorian Review, 36 (Fall 2010) 2: 32-36. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41413848?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

Evelleen Richards, “The ‘Moral Anatomy’ of Robert Knox: The Interplay between Biological and Social Thought in Victorian Scientific Naturalism,” Isis 85 (1994) 3: 377–411.

Efram Sera-Shriar, The Making of British Anthropology, 1813-1871 (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2013), 81-107.

George W. Stocking, Jr., Victorian Anthropology (New York: Free Press, 1987).