James Hunt

James Hunt, along with Richard Francis Burton, founded the Anthropological Society of London in 1863 out of frustration at the reluctance of the Ethnological Society of London (one of whose founders was James Cowles Prichard) to explore the social significance of racial differences or to credit the importance of the physical as well as the cultural aspects of humanity. Hunt’s new organization quickly developed a large membership, with audiences for events such as the 1864 presentation by Alfred Russel Wallace numbering in the hundreds.

In that presentation, Wallace had tried to reconcile both monogenetic and polygenetic accounts of human origins by folding them into a Darwinian model of evolution, but Hunt had little patience with equivocation. A committed polygenist, he opposed the doctrine already known as “Darwinism” as monogenism in disguise, despised Huxley, and deeply admired Robert Knox (“Race is everything”), whom he had served as secretary at the Ethnological Society. He renounced any interest in the question of human origins and rejected the Bible as a source of scientific authority. (After Hunt’s death, the Anthropological Society continued its hostility to Darwinism. The Society’s official journal took no notice at all of Darwin’s Descent of Man on its appearance in 1871). And, most importantly, Hunt rejected any suggestion of the psychic unity of mankind and therefore of even a potential or metaphysical equality between the races of the kind proposed by Prichard and others. In the 1863 speech from which the selections printed below are taken, he also mentioned, and dismissed, Prichard’s 1813 assertion that humanity originated in Africa (p. 3).

Like other anthropologists at the time, especially in the “American School,” Hunt felt that an inquiry into human “types” provided a scientific way of addressing significant social issues. His address, titled “On the Negro’s Place in Nature,” focused on the issue that divided the Anthropological Society and its predecessor organization, the Negro question. The published address found sympathetic readers both in England and in the United States, where it was issued the following year in an anti-abolitionist series. The publisher of that series, J. H. Van Evrie, had himself weighed in on the issue, authoring an 1853 pamphlet that he subsequently expanded into a 339-page book whose argument can be deduced from the title: Negroes and Negro “Slavery:” The First an Inferior Race: The Latter Its Normal Condition.* Van Eyrie also contributed a preface to Hunt’s lecture in which he celebrated Hunt as a man who “has collected all the reliable modern authorities, and demonstrates what every unperverted American knows —that the Negro is a different and subordinate species or race.”

Under Hunt’s leadership, the Anthropological Society, which became known as the “Cannibal Club,” endorsed the use of brutal means of suppressing the rebels in the Jamaica uprising of 1865, argued that governmental differences in Ireland should be solved by implementing racial doctrine concerning Saxons and Celts, and supported the South in the American Civil War. (A 2009 book asserts that Hunt was, during the war, a paid agent of the Confederacy, tasked with influencing London opinion in favor of the South.**) In Hunt’s work, we can see a drastic narrowing of the scientific inquiry into race from a global study of the peoples of the world, which dominated the first half of the nineteenth century, to an exclusive focus on the differences between Europeans and Negroes that would become increasingly prominent especially in the United States in the second half of the century.

Hunt’s convictions on the subject of race involved him, and the Anthropological Society, in a number of political disputes, but in this address he presents his views as the consequence of hard empirical and scientific work, citing Blumenbach, Quatrefages de Bréau, Bory de St.-Vincent [see Cuvier], Soemmering, Morton, Prichard, Lawrence, Nott, Vogt, Hamilton Smith, Broca, and Charles Lyell, as well as traveler’s reports and craniological studies—all of which he construes as ultimately supporting, or at least not disproving, the argument that the Negro “belongs to a distinct type of Man to the European.” The assertion of the proximity of the Negro to the ape, while controversial, was not out of the mainstream of European or American thought; indeed, it was a cliché endlessly recycled in journalism, textbooks, and scientific studies.

Hunt does not pronounce on the question of species difference only because “the word ‘species,’ in the present state of science is not satisfactory.” But his use of the word “type” suggests a conceptual possibility that others, including Cuvier, Vogt, Topinard, Ripley and other polygenists would exploit as a way of avoiding the fact that races could not be identified as discrete or isolated groups. [On “types,” see Odom in Further Reading.]

Like Knox, Hunt takes a (qualified) stand against slavery, an evil practice whose most degraded forms were, he asserts, to be found in Africa itself and constituted further proof of the Negro’s “natural subordination” and general unfitness for civilization. There was, he said, only one justification for Negro slavery in America, and that was philanthropic—that the conditions in Africa were so desolate that enslaved Africans were better off and even happier than they had been in their homeland.

Hunt maintained his position on Negro—by which he meant “the typical woolly-headed Negro”; he was aware that Africa contained many races—inferiority despite his awareness that, as both Nott and Morton had noted, “the Negroes in America are undergoing a manifest improvement in their physical type,” even becoming “more intelligent” generation by generation. When in the early twentieth century the anthropologist Franz Boas demonstrated alterations in the bodies of the children of immigrants, his results were considered to strike a mortal blow to the kind of racial ranking that Hunt, like Nott and Morton, advocated. Dying at the age of thirty-six in 1869, Hunt did not live to recant or modify his views.

The responses to Hunt’s 1863 talk were published in the Journal of the Anthropological Society later that year. While broadly appreciative of Hunt’s efforts, members of the audience raised a number of questions: whether whites had “any right whatever to enslave their brother”; whether “the African” was the same as “the Negro”; whether the Negro could “be educated up to the European”; and whether the Negro was a different “species” from the European.***

Hunt was a vehement, contentious, and difficult man. His entry in the Dictionary of National Biography concludes by saying, “Without being profound, he was a serious student, who did much to place anthropology on a sound basis; but his freedom of speech, quick temper, and sceptical views on religion roused much personal hostility.”

* J. H. Van Evrie, Negroes and Negro “Slavery:” The First an Inferior Race: The Latter Its Normal Condition (New York: Van Evrie, Horton & Co., 1861); at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=loc.ark:/13960/t0ms3tn8r&view=1up&seq=9&skin=202

**Adrian Desmond, James Moore, Darwin’s Sacred Cause: Race, Slavery, and the Quest for Human Origins (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), p. 332-3.

***Journal of the Anthropological Society of London, vol. 2 (1864), xv-lvi. At: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3025197

“On the Negro’s Place in Nature”

I propose in this communication to discuss the physical and mental characters of the Negro, with a view of determining not only his position in animated nature, but also the station he should occupy in the genus Homo. I shall necessarily have to go over a wide field and cannot hope to treat the subject in an exhaustive manner. I shall be amply satisfied if I succeed in directing the attention of my scientific friends to a study of this most important and hitherto nearly neglected branch of study in the great science of Anthropology.

It is not a little remarkable that the subject I propose to bring before you this evening is one which has never been discussed before a scientific audience in this Metropolis. In France, in America, and in Germany, the physical and mental characters of the Negro have been frequently discussed, and England alone has neglected to pay that attention to the question which its importance demands. . . . Although I shall dwell chiefly on the physical, mental and moral characters of the Negro, I shall, at the same time, not hesitate to make such practical deductions which appear to be warranted from the facts we now have at hand, and trust that a fair and open discussion of this subject may eventually be the means of removing much of the misconception which appears to prevail on this subject both in the minds of the public, and too frequently in the minds of scientific men. . . .

In the first place, I would explain that I understand by Negro, the dark, woolly-headed African found in the neighborhood of the Congo river. Africa contains, like every other continent, a large number of different races; and these, having become very much mixed, may be estimated as a whole at about 150 millions, occupying a territory of between 13 and 14 millions of square miles. I shall not enter into any disquisition as to the great diversity of physical conformation that is found in different races, but shall simply say that my remarks will be confined to the typical woolly-headed Negro. Not only is there a large amount of mixed blood in Africa, but there are also apparently races of very different physical characters, and in as far as they approach the typical Negro, so far will my remarks apply to them. But I shall exclude entirely from consideration all those who have European, Asiatic, Moorish or Berber blood in their veins.

My object is to attempt to determine the position which one well-defined race occupies in the genus Homo, and the relation or analogy which the Negro race bears to animated nature generally.— We have heard discussions recently respecting Man’s place, in nature; but it seems to me that we err in grouping all the different races of Man under one generic name, and then comparing them with the Anthropoid Apes. If we wish to make any advance in discussing such a subject, we must not speak of man generally, but must select one race or species, and draw our comparison in this manner. I shall adopt this plan in comparing the Negro with the European as represented by the German, Frenchman or Englishman. Our object is, not to support some foregone conclusion, but to endeavor to ascertain what is the truth, by a careful and conscientious examination and discussion of the facts before us. In any conclusion I may draw respecting the Negro’s character, no decided opinion will be implied as to the vexed question of man’s origin. If the Negro could be proved to be a distinct species to the European, it would not be proved that they had not the same origin—it would only render their identity of origin less likely. I shall, also, have to dwell much on the analogies existing between the Negro and the Anthropoid Apes; but these analogies do not necessarily involve relationship. The Negro race in some of its characters, is the lowest of existing races, while in others it approaches the highest type of European; and this is the case with other savage races. . . . It is too generally taught that the Negro only differs from the European in the color of his skin and the peculiarity of his hair; but such opinions are not supported by facts. The skin and hair are not the only things which distinguish the Negro from the European, even physically; and the difference is greater, mentally and morally, than the demonstrated physical difference. In the first place, what are the physical distinctions between the Negro and the other races of man?

The average height of the Negro is less than the European, and although there are occasionally exceptions, the skeleton of the Negro is generally heavier, and the bones larger and thicker in proportion to the muscles, than those of the European. The bones are also whiter, from the greater abundance of calcerous salts. The thorax is generally laterally compressed, and, in thin individuals, presents a cylindrical form, and is smaller in proportion to the extremities. The extremities of the Negro differ from other races more by proportion than by form; the arm usually reaches below the middle of the femur. The leg is on the whole longer, but is made to look short on account of the ankle being only between 1¼ in. to 1½ in. above the ground. This character is often seen in mulattoes. The foot is fiat and the heel is both fiat and long. Burmeister has pointed out the resemblance of the foot and the position of the toes of the Negro to those of the ape. The toes are small, the first separated from the second by a free space. Many observers have noticed the fact that the Negro frequently uses the great toe as a thumb. The knees are rather bent, the calves weak, and the upper part of the thigh rather thin. The upper thighbone of the Negro has not so decided a resemblance to the ape as that of the bushman. He rarely stands quite upright, his short neck and large development of the cervical muscles give great strength to the neck; enabling him to fight like a ram, or carry large weights on his head. The shoulders, arms, and legs are all weak in comparison. The hand is always relatively larger than in the European. The palm is flat, thumb narrow, long, and very weak

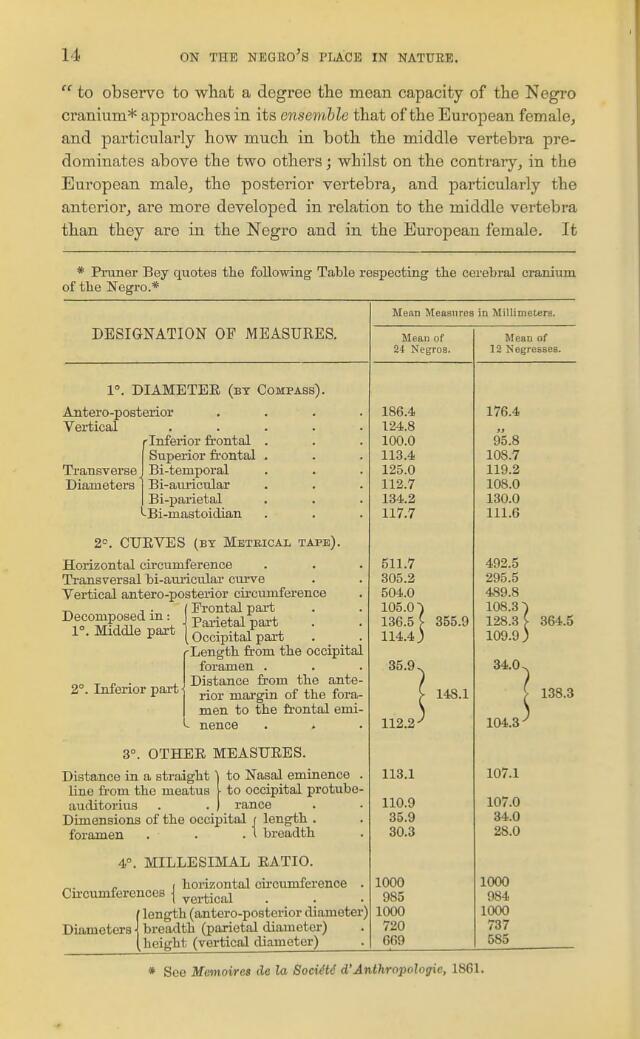

It appears from a table prepared by Dr. Pruner Bey, that the humerus and the femur in the Negro and European, of equal height, are shorter in the Negro than in the European; while the tibia, the foot, the radius, and the hand, are more elongated than in the Negro race. That the fingers and arms are longer has long been affirmed, but we have to thank Dr. Pruner Bey for the absolute proof.

The great distinguishing characters of the Negro are the flattened forehead, which is low and compressed. The nose and whole face is flattened, and the Negro thus has a facial angle generally between 70 and 75 degrees, occasionally only 65 degrees. The nasal cavities and the orbits are spacious. The skull is very hard and unusually thick; enabling the Negroes to fight or carry heavy weights on their heads with pleasure. The coronal region is arched, but not so much developed as in the European women. The posterior portion of the skull is increased, however, in proportion to that of the anterior being diminished. But M. Gratiolet has shown that the unequal development of the anterior lobes is not the sole cause of the psychological inequalities of the human races. The same scientific observer has also stated that in the superior or frontal races, the cranial sutures close much earlier than in the inferior or occipital races. The frontal races he considers superior, not simply from the form of the skull, but because they have an absolutely more voluminous brain. The frontal cavity being much larger than the occipital, a great loss of space is caused by the depressing of the anterior region, which is not compensated for by the increase of the occipital region. M. Gratiolet has also observed that in the anterior races the sutures of the cranium do not close so early as in the occipital or inferior races. From these researches it appears that in the Negro the growth of the brain is sooner arrested than in the European. This premature union of the bones of the skull may give a clue to much of the mental inferiority which is seen in the Negro race. There can be no doubt that in puberty a great change takes place in relation to physical development; but in the Negro there appears to be an arrested development of the brain, exactly harmonizing with the physical formation. Young Negro children are nearly as intelligent as European children; but the older they grow the less intelligent they become. They exhibit, when young, an animal liveliness for play and tricks, far surpassing the European child. The infant ape’s skull resembles more the Negro’s head than the aged ape, and thus shows a striking analogy in their craniological development. . . . But the most satisfactory researches on this point are those made by the late Dr. Morton, of America, and his successor, Dr. J. A. Meigs, of Philadelphia. Dr. Meigs, in following out the researches of his predecessor, has found that in size of the brain, the Negro comes after the European, Finn, Syro-Egyptian, Mongol, Malay, the Semitic, American Indian, and the Esquimaux; but that the brain of the Negro race takes precedence of the ancient civilized races of America, the Egyptian of all periods, the Hindoo, the Hottentot, the Australian, and the Negroes of Polynesia. Thus we see that the Negro has at least six well-defined races above him and six below him, taking the internal cavity of the brain as the test. . . .

There seems to be, generally, less difference between the Negro and Negress, than between the European male and female; but on the other hand, the Negress, with the shortened numerus, presents a disadvantage “which one might be tempted to look at as a return to the animal form.” Lawrence says, “the Negro structure approaches unequivocally to that of the ape;” while Bevy [sic] St. Vincent, and Fischer do not greatly differ in their description of the anatomy of the Negro, to the facts I have adduced.

It cannot be doubted that the brain of the Negro bears a great resemblance to a European woman or child’s brain, and thus approaches the ape far more than the European, while the Negress approaches still nearer to the ape.

With regard to the chemical constituents of the brain of the Negro, little positive is yet known. It has been found however, that the grey substance of the brain of a Negro is of a darker color than that of the European, that the whole brain is of a smoky tint, and that the pia mater contains brown spots, which are never found in the brain of a European. H. Broca has recently had an opportunity of confirming the truth of this statement. With regard to the convolutions there is unanimous testimony that the convolutions of the brain of the Negro are less numerous and more massive than in the European. Waitz thinks that the only resemblance of the Negro's brain to that of the ape is limited to this point. Some observers have thought they have detected a great resemblance between the development of the temporal lobe in the Negro and ape; but much further observation is required on this important subject.

In the negro race there is a great uniformity of temperament. In every people of Europe all temperaments exist; but in the Negro race we can only discover analogies for the choleric and phlegmatic temperaments. The senses of the Negro are very acute, especially the smell and taste; but Pruner Bey says that there has been much exaggeration as to the perfection of the senses of the Negro, and that their eye-sight, in particular, is very much inferior to the European. The most detestable odors delight him, and he eats everything.

I am astonished that an Ethnologist, a student of the Science of the Races of Man, could deliberately make the statement that all races have the same intellectual, moral and religious natures. Rather the reverse is the real fact. Intelligence is the great peculiarity of man, and it is in the instincts of each race that we find the greatest difference. Mr. Dunn, however, it must be acknowledged, does not carry out the principle he here enunciates, for he fully admits the fact that, principally, Negro children cannot be educated with the whites. He also admits that some of the lower races are not able to receive complex ideas, or have little power of thinking and none of generalization, although they have excellent memories. The assertion that the Negro only requires an opportunity for becoming civilized is disproved by history. The African race have had the benefit of the Egyptian, Carthagenian, and Roman civilizations, but nowhere did they become civilized. Not only have the Negro race never civilized themselves, but they have never accepted any other civilization. No people have had so much communication with Christian Europeans as the people of Africa, where Christian bishops existed for centuries. They possess some knowledge of metallurgy, but no other arts; their rude laws seem to have been borrowed and changed to suit their peculiar instincts. With the Negro, as with some other races of man, it has been found that the children are precocious, but that no advance in education can be made after they arrive at the age of maturity; they still continue mentally children. The dark races generally do not accept the civilization which surrounds them, as is shown in the South Sea, where they remain the uncivilized race by the side of the Halays. The opinion of Dr. Channing, of America, is often quoted respecting the Negro. He says: “I would expect from the Negro race, when civilized, less energy, less courage, less intellectual originality, than in ours; but more amiableness, tranquility, gentleness, and content.” Now, if possible to civilize them, there is no doubt they would show less energy, less courage, and intellectual originality (of which they would be utterly defficient;) and as to their amiableness, tranquility, gentleness, and content, it would be more like the tranquility and content shown by some of our domestic animals than anything else to which we can compare it. It has been said that the present slaveholders of America “no more think of rebellion amongst their full-blooded slaves than they do of rebellion among their cows and horses.” It has also been affirmed (and I believe it the truth) that not a single soldier has been required to keep order in the Slave States.

We now know it to be a patent fact that there are races existing which have no history, and that the Negro is one of these races. From the most remote antiquity the Negro race seems to have been what they now are. We may be pretty sure that the Negro race have been without a progressive history and that they have been for thousands of years the uncivilized race they are at this moment. Egyptian monuments depict them the inferior race they are at this minute, and holding exactly the same position to the European. Morton truly observes: “Negroes were numerous in Egypt, but their social position in ancient times was the same that it is now, that of servants and slaves.

On this point [the alteration in appearance and demeanor of the descendants of Africans brought to the United States as slaves] Dr. Nott has very judiciously observed: “Sir C. Lyell, in common with tourists less eminent, but on this question not less misinformed, has somewhere stated that the Negroes in America are undergoing a manifest improvement in their physical type.—He has no doubt that they will, in time, show a development in skull and intellect quite equal to the whites. This unscientific assertion is disproved by the cranial measurements of Dr. Morton. That Negroes imported into, or born in the United States become more intelligent and better developed in their physique generally than their native compatriots of Africa, every one will admit: but such intelligence is easily explained by their ceaseless contact with the whites, from whom they derive much instruction; and such physical improvement may also be readily accounted for by the increased comforts with which they are supplied. In Africa, owing to their natural improvidence, the Negroes are more frequently than not a half-starved, and therefore half-developed race; but when they are regularly and adequately fed, they become healthier, better developed, and more humanized. Wild horses cattle, asses and other brutes are greatly improved in like manner by domestication; but neither climate nor food can transmute an ass into a horse, or a buffalo into an ox.”

The real facts seem to be, that the Negroes employed in domestic labor have more intelligence than those who are employed at field labor, who are nearly in the same state of intelligence as when they left Africa. We see, therefore, in this improvement of the Negro, simply the effect of education, but not of climate or other physical agents. We fully admit that the domestic Negro is improved in intelligence in America, resulting from the imitation of the sayings and doings of the superior race by which he is surrounded; but much of this improvement is owing to the mixture of European and Negro blood. The pure Negro is true to his character, and it is said that he is no sooner taught to read than he will take every chance of reading his master’s letters; and if he be taught to write, he will soon learn to forge his master’s signature. This applies with equal and perhaps greater force to those free, semi-civilized Negroes who are held by some in such theoretical veneration.

Of all the questions connected with the Negro, the most difficult to settle is that of his intelligence. Amidst conflicting testimony, it is difficult to discover the truth. We may admit, however, that there are instances of the pure Negro showing great powers of memory, such as the acquirement of languages; but we must also remember that memory is one of the lowest mental powers. Numerous instances have been collected by different partisan writers to show that the Negro is equal, intellectually, to the European; but an examination of these cases nearly invariably leads to the conclusion that there has been much exaggeration in the statements made by writers as to the aptitude of the Negro for education and improvement. . . .

Surely, if there is equality in the mental development of human races, some one instance can be quoted. From all the evidence we have examined, we see no reason to believe that the pure Negro even advances further in intellect than an intelligent European boy of fourteen years of age.

Consul Hutchinson, who spent no less than eighteen years on the West Coast of Africa, and who is as competent a judge as any man now living, says, that “his own observations on the African tribes tend to show that the African is not exactly the style of ‘man and a brother’ which mistaken enthusiasts for his civilization depict him to be.” He gives the result of a ten years’ attendance at the Missionary school at Cape Palmas of one of his servants, a Kruman, and says that at the end he was asked what he knew of God? He replied: “God be very good; He made two things— one sleep and the other Sunday, when no person had to work.” Consul Hutchinson says that “the thirst for each other’s blood, which seems a daily habit amongst too many of the Negro tribes in Western Africa, appears to me to be incompatible with ordinary notions of common humanity.” He adds that for scores of years European missionaries and English traders have mixed with them in social intercourse, yet they still cling “to their gris-gris, jujus, fetichism and cannibalism with as much pertinacity as they did many hundred years ago.” He adds: “Here we have all the appliances of our arts, our science, and our Christianity, doing no more good than did the wheat in the parable that was sown amongst the briars and the thorns. To attempt civilizing such a race before they are humanized appears to me to be beginning at the wrong end. I have passed many an hour in cogitating and endeavoring to fabricate some sort of education likely to root out the fell spirit that dictates human sacrifices and cannibalism; but I fear years must elapse before any educational principle, in its simplest form, can produce an amendment on temperaments such as they possess.”

Colonel Hamilton Smith thus describes the Negro: “The Negro is habitually dormant, but when roused shows his emotion by great gesticulations, regardless of circumstances. War is a passion that excites in them a brutal disregard of human feelings; it entails the deliberate murder of prisoners, and victims are slain to serve the manes of departed chiefs. Even cannibalism is frequent among the tribes of the interior. Notwithstanding the listless torpidity caused by excessive heat, the perceptive faculties of the children are far from contemptible; they have a quick apprehension of the ridiculous, often surpassing the intelligence of the whites, and only drop behind them about the twelfth year, when the reflective powers begin to have the ascendancy. Collectively, the untutored Negro mind is confiding and single-hearted, naturally kind and hospitable. Both sexes are easily ruled, and appreciate what is good under the guidance of common justice and prudence. Yet where so much that honors human nature remains in apathy, the typical woolly-haired races have never invented a reasoned theological system, discovered an alphabet, framed a grammatical language, nor made the least step in science or art. They have never comprehended what they have learned, nor retained a civilization taught them by contact with more refined nations as soon as that contact had ceased. They have at no time formed great political states, nor commenced a self-evolving civilization. Conquest, with them, has been confined to kindred tribes, and produced only slaughter. Even Christianity, of more than three centuries’ duration in Congo, has scarcely excited a progressive civilization. Thus, even the good qualities given to the Negro by the bounty of nature, have seemed only to make him a slave trodden down by every remorseless foot, and to brand him for ages with the epithet of outcast—the marked unceasing proof of a curse as old as the origin of society, not even deserving human forbearance. And true it is that the worst slavery is his lot even at home, for he is there exposed to the constant peril of becoming also a victim, slaughtered with the most revolting torments. Tyrant of his blood, he traffics in slavery as it were merchandise, makes war purposely to capture neighbors, and sells even his own wives and children.”

Carl Vogt has recently observed: “Most of the characters of the Negro viewed externally remind us irresistibly of the ape; the short neck, the long lean limbs, the projecting pendulous belly, all this affords a glimmer of the ape beneath the human envelope . . . .”

Mr. Winwood Reade says, “It must be acknowledged, that putting all exceptions aside, the women of Africa are very inferior beings. Their very virtues, with their affections and their industry, are those of well trained domestic animals. But if the women of Africa are brutal, the men of Africa are feminine. Their faces are smooth, their breasts are frequently as full as those of European women; their voices are never gruff or deep. Their fingers are long; and they can be very proud of their rosy nails.—While the women are nearly always ill-shaped after their girlhood, the men have gracefully moulded limbs, and always are after a feminine type—the arms rounded, the legs elegantly formed, without too much muscular development, and the feet delicate and small. . . . A king of Ashanti cut off the hands of a slave, and had her scratch his head for vermin with the stumps. If any one had accused him of barbarity he would not have understood the accusation. It was his idea of a good practical joke.” He continues, “It will be understood that the typical Negroes with whom the slavers are supplied, represent the dangerous, the destitute, and the diseased classes of African society. They may be compared to those which in England fill our gaols, our work-houses, and our hospitals. So far from being equal to us, the polished inhabitants of Europe, as some ignorant people suppose, they are immeasurably below the Africans themselves. The typical Negro is the true savage of Africa, and I must paint the deformed anatomy of his mind as I have already done that of His body. The typical Negroes dwell in petty tribes where all are equal, except the women, who are slaves; where property is common, and where, consequently, there is no property at all; where one may recognize the Utopia of philosophers, and observe the saddest and basest spectacles which humanity can afford. The typical Negro, unrestrained by moral laws, spends his days in sloth and his nights in debauchery. . . . They do not merit to be called our brethren; but let us call them our children. Let us educate them carefully, and in time we may elevate them; but not to our level—that, I fear, can never be—but to the level of those from whom they have fallen.” This last remark is made in the supposition that they typical Negro is degenerated from some higher African race; but we think such an hypothesis is not warranted by history, archeology, or any well established facts.

M. Pruner Bey, one of the most eminent of living Anthropologists, has written the most complete memoir on the Negro, yet published, and this author must, for some time to come, be the supreme authority on this subject. Many years ago he thus expressed himself respecting the psychological character of the Negro: “The capacity of the Negro is limited to imitation. The prevailing impulse is for sensuality and rest. No sooner are the physical wants satisfied all physical effort ceases, and the body abandons itself to sexual gratification and rest. The family relations are weak; the husband or father is little concerned. Jealousy has only carnal motives, and the fidelity of the female is secured by mechanical contrivances. Drunkenness, gambling, sexual gratification, and ornamentation of the body are the most powerful levers in the life of the Negro. The whole industry is limited to ornaments. Instead of clothing himself, he ornaments his body. Like certain animals, the Negro seems apathetic under pain. The explosions of passions occur when least expected, but are not lasting. The temperament of the Negro has been called choleric, but it is only so to a certain extent. It is a momentary ebulition, followed instantly by perfect apathy. Life has for the Negro no longer any value when he cannot supply the physical wants. He never resists by increased activity, but prefers to die in a state of apathy, or he commits suicide. The Negro has no love for war; he is only driven to it by hunger. War, from a passion or destructiveness, is unknown to him.” This is a sufficiently clear and truthful picture, and the following summary, with which M. Bey concluded his paper, presented to the Paris Anthropological Society, is equally to be commended for its truth and moderation: “The Negro has always appeared to me as partaking of the nature both of the child and the old man. Anatomists worthy of our confidence—Jacquart, Serres, and Huschke—have in this sense, interpreted the details of the anatomy of the Negro. The elongated form of the cranium, the proportions of the cerebral lobes and their respective forms, the prominence of the inferior border of the orbits, the flattened nose, the rounded larynx, the less marked curves of the verteabral column, the lateral compression of the thorax and pelvis, with the vertical direction of the iliac bones, the elongated neck of the uterus, the proportion of the parts composing the extremities, the relative simplicity of the cerebral convolutions, &c., are characteristic features of the Negro race, which are found in the foetus or the infant of the Aryan race, in the different periods of development. The propensity for amusements, for material enjoyments, for imitation, and the inconstancy of affection, are the appendages of the Negro as well as of our children. The flexuosity of the arteries, the flattening of the cornea, the weakness of the muscles, the dragging walk, and the early obliteration of the cranial sutures, the obstinacy and love of repose, are met with in the Negro as in our aged men. In short, the great curve of human development, and its backward direction, appear to be sufficiently extended to appreciate the differences characterising the Negro race opposed to our race, always taking into account the differential characters resulting from adaptation to external conditions. If our interpretation leaves open many gaps, the future may fill them up, perhaps, in the same sense. If, finally, the Negro, speaking always figuratively, partakes of the nature of the ape, it must still be admitted that it is not the most ferocious, malicious, nor the most pernicious, but rather the most patient, and frequently the most useful animal. In any case, an honorable mediocrity is his inheritance.”

The general deductions we would desire to make are: 1. That there is as good reason for classifying the Negro as a distinct species from Europeans as there is for making the ass a distinct species from the zebra; and if we take into consideration in classification, there is a far greater difference between the Negro and European than between the gorilla and chimpanzee. 2. That the analogies are far more numerous between the Negro and apes than between the European and apes. 3. That the Negro is inferior intellectually to the European. 4. That the Negro is more humanized when in his natural subordination to the European than under any other circumstances. 5. That the Negro race can only be humanized and civilized by Europeans. 6. That European civilization is not suited to the Negro requirements or character.

No man who thoroughly investigates with an unbiassed mind, can doubt that the Negro belongs to a distinct type of Man to the European. The word “species,” in the present state of science is not satisfactory; but we may safely say that there is in the Negro that assemblage of evidence which would, ipso facto, induce an unbiassed observer to make the European and Negro two distinct types of man.

The facts I have quoted I believe are sufficient to establish the fact that the Negro is inferior intellectually to the European, and that the analogies are far more numerous between the ape and the Negro than between the ape and the European.

It may be said that some of the propositions I have advanced are in favor of the slave trade. Such, however, is not my own interpretation of these propositions. No one can be more conscious of the horrors of the “slave trade” as conducted at this time. Nothing can be worse for Africa generally than the continual capture of innocent men and women by brutal Europeans. Few things can be more horrible than the manner in which these people are attempted to be carried across the Atlantic. Nay, more, nothing can be more unjust than to sell any man, woman, or child into “slavery,” as understood by the Greeks and Romans, where the life of the slave was absolutely at the disposal of the master whenever his caprice or fancy thought fit to take it. We protest against being put forward as advocating such views.

But while I say this, I cannot shut my eyes to the fact that slavery, as understood by the ancients, does not exist out of Africa, and that the highest type of the Negro race is at present to be found in the so-called Slave States of America. Far superior in intelligence and physique to both his brethren in Africa and to his “free” brethren in the Federal States, nowhere does the Negro attain such a long life as in the Confederate States, and this law formerly obtained in the West India Islands before our mistaken interference. Nowhere does the Negro character shine so highly as it does in his childish and fond attachment to his master and his family. The Negro cares far more for his master and mistress than he does for his own children after they are a few years old. I by no means join in that indiscriminate abuse of the Negro character which has been indulged in, especially by those who have only seen the Negro in his savage state, or the “emancipated” (from work?) in the West India Islands. On the contrary, there is much that is to be admired, and more that is useful in the Negro, when properly and kindly treated. Brutal masters there are in every part of the world: but we must not found a law on exceptions. Scientific men, therefore, dare not close their eyes to the clear facts, as to the improvement in mind and body, as well as the general happiness, which is seen in those parts of the world in which the Negro is working his natural subordination to the European. In some respects, the Negro is certainly not only not inferior, but even far superior to the European. If, for instance, the European was alone in the Confederate States of America, those fertile regions would soon become a barren waste. The Negro is there able to work with impunity, and does himself and the world generally much good by his labor. Occupations and diseases which are fatal to the Europeans are quite harmless to the Negro. By their juxtaposition in this part of the world they confer a material benefit on each other.

In now bringing my remarks to a close, I cannot, perhaps, do better than quote the graphic picture of the present state of Africa, which has been only published during the last few weeks. There is much true science and healthy manhood in these sentiments. The work of which I speak is evidently the work of a man who has devoted much attention to the study of the great science of mankind; and I am pleased to find that my own views find ample support in the conclusions of this accomplished and scientific observer. Speaking of the Negroes of Bonny, he says: “The slaves wore a truly miserable appearance, lean and deformed, with krakra lepra and fearful ulcerations. It is in these places that one begins to feel a doubt touching the total suppression of slavery. The chiefs openly beg that the rules may be relaxed, in order that they may get rid of their criminals. This is at present impossible, and the effects are a reduplication of misery. We pamper our convicts; Africans torture them to death. Cheapness [of] the human article is another of [the causes] of immense misery to it. In some rivers a canoe crew never lasts three years. Pilfering—’Show me a black man and I will show you a thief,’ say the traders—and debauchery are natural to the slave, and they must be repressed by abominable cruelties. The master thinks nothing of nailing their hands to a water cask, of mutilating them in various ways; many lose their eyes by being peppered, after the East Indian fashion, with coarsely-powdered cayenne, their ears are cut off, or they are flogged. The whip is composed of a twisted bullock’s or hippopotamus’ hide, sun dried, with a sharp edge at the turns, and often wrapped with copper wire; it is less merciful even than the knout, now historical. The operation may be prolonged for hours, or for a whole day, the culprit’s arms being tied to a rafter, which keeps them at full stretch, and every fifteen minutes or so a whack, that cuts away the flesh like a knife, is administered. This is a favorite treatment for guilty wives, who are also ripped up, cut to pieces, or thrown to the sharks. If a woman has twins, or becomes mother of more than four, the parent is banished and the children are destroyed. The greatest insult is to point at a man with arm and two fingers extended, saying at the same time, Nama shubra! i.e. , one of twins, or a son of some lower animal. When a great man dies, all kinds of barbarities are committed; slaves are buried, or floated down the river bound to bamboo sticks and mats, till eaten piece-meal by sharks. The slave, as might be expected, is not less brutal than his lord. It amazes me to hear Englishmen plead that there is moral degradation to a Negro bought by a white man, and none when serving under a black man. The philanthropists, doubtless, think how our poorer classes at home, in the nineteenth century, would feel if hurried from liberty to eternal servitude by some nefarious African. But can any civilized sentiments belong to the miserable half-starved being, whose one scanty meal of vegetable per day is eked out with monkey and snake, cat and dog, maggot and grub—whose life is ceaseless toil, varied only by torture, and who may be destroyed at any moment by a nod from his owner? When the slave has once surmounted his dread of being shipped by the white man, nothing under the sun would, I believe induce him willingly to return to what he should call his home.”

Herbert H. Odom, “Generalizations on Race in Nineteenth-Century Physical Anthropology,” Isis 58 (Spring, 1967) 1: 4-18.

Ronald Rainger. “Race, Politics, and Science: The Anthropological Society of London in the 1860s,” Victorian Studies 22 (Autumn, 1978): 51-70.

George W. Stocking, Jr., Race, Culture, and Evolution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968), 42-68.

George W. Stocking, Jr., Victorian Anthropology (New York: Free Press, 1987).