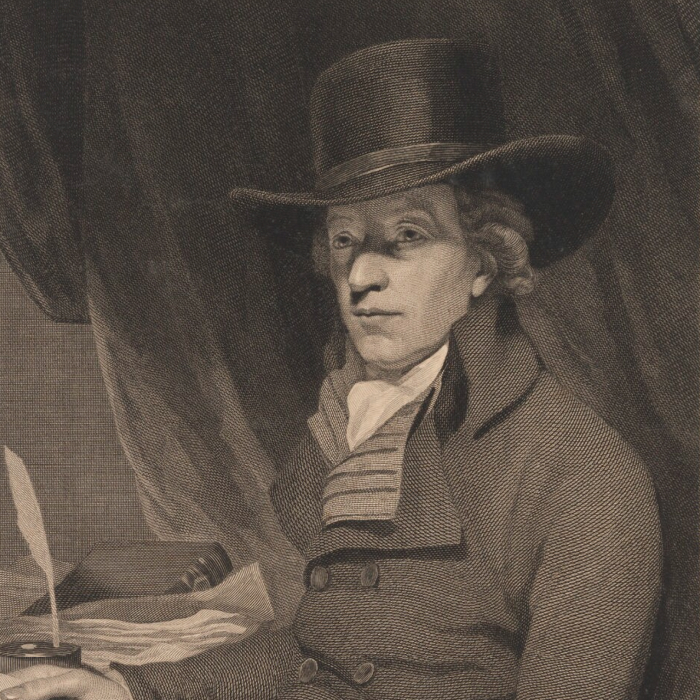

Edward Long

Edward Long, a colonial administrator whose family had lived on the island of Jamaica since the English defeated the Spanish in 1665, compiled a massive, three-volume account of the island’s history, geography, economy, governance, and social structure from 1665 to 1774. This work was the first and for over two hundred years the standard Anglophone history of the island, and stands as a monument to colonial historiography as well as a testament to Jamaican prosperity and confidence.

For more recent readers, much of the interest in this text derives from Long’s vigorously phrased reflections on the Negroes who were brought to the island as slaves after many of the original inhabitants had been killed by the Spanish or by the diseases brought by the Spanish to which they had no immunity. Slaves were indispensable to the island economy, which was driven by the European demand for cotton, sugar cane, tobacco, and other crops. Because they were so essential to the prosperity of their owners, slaves were, Long argues, treated with greater kindness and consideration than the poor of England ever received. Writing in the aftermath of the stunning event of Tacky’s Revolt of 1760, a massive slave uprising on the island, Long undertakes a defense of slavery that was not merely economic but moral as well. His reflections on the ontology of the Negro were understood by both Long and many of his readers to constitute a significant, if controversial, contribution to a theory of race and racial difference.

As a slave owner on a Caribbean plantation island and a member of the Creole elite on the island, Long, who had been educated in England before moving to Jamaica at the age of twenty-four, had a practical interest in the subject of race. Indeed, part of his defense of slavery grows out of his experience managing a large number of slaves. Beyond his personal experience, however, Long took a theoretical interest in the subject. Conversant with advanced social and philosophical discourse in Europe, Long was keenly aware of the moral considerations, scientific conclusions, and theoretical distinctions pertaining to slavery that were current in advanced European intellectual culture of the time. Conversant with the work of Buffon, Hume, Voltaire, and many others, Long derived from his reading the conceptual resources he needed to justify and defend the practice of chattel slavery on the basis of racial ontology.

Long’s defense of slavery is not based on the superior moral character of the white man. He begins the Introduction to Volume I by admitting “consummate tyranny and injustice, practised in these remote parts of the British empire,” and conceding that, in fact, “a faithful description of our Provincial governors, and men in power, would be little better than a portrait of artifice, duplicity, haughtiness, violence, rapine, avarice, meanness, rancour, and dishonesty, ranged in succession; with a very small portion of honour, justice, and magnanimity, here and there intermixed, to lessen the disgust, which, otherwise, the eye must feel in the contemplation of so horrid a group” (4). Part of the horror, for Long, is the disturbingly common practice of interracial sex: “Many are the men, of every rank, quality, and degree here, who would much rather riot in these goatish embraces, than share the pure and lawful bliss derived from matrimonial, mutual love” (Bk. II, Ch. XIII, 328).

Both in itself and in its consequences, interracial sex threatened the racial categories on which Long based his non-economic argument for slavery. Linnaeus argued that simians and humans were different species of the same genus, but Long makes a comparable distinction between Negroes and whites, offering as proof the diminished fertility of mulattos, which he claims to have observed in Jamaica. [For refutation of this argument, see Firmin.] The lack of precision in the concept of race enables Long to use the term as the name for a division almost, or perhaps, as deep and decisive as the concept of species in Linnaeus. Drawing on the concept of the “chain of being” and citing as if it were a conclusion based on personal observation Hume’s tentative footnote concerning Negro inferiority in “Of National Characters,” Long places Negroes at the lowest point of the human, adjacent to the oran-outang, whose grotesque resemblance to humans makes him seem more a “wild man” than an ape, and “fills up the space” between humans and primates (363). At this lowest point of the human, sex once again confounds the categories: as Long notes, there are creditable accounts of intercourse between Negroes and oran-outangs. “Ludicrous as the opinion may seem,” Long writes, “I do not think that an oran-outang husband would be any dishonour to an Hottentot female” (365).

If unsanctioned sexuality represents a problem for categorization, it can also be the solution that preserves or restores the order of things on which plantations depend. Long begins Vol. II, Book II, Chapter XIII with a very detailed account of how, over the course of six generations, the descendants of a white man and a Negro woman living in “the Spanish colonies” can “mend the breed by ascending or growing whiter,” a process that can be accomplished in only three generations in Jamaica, where the distinctions between Mulatto, Terceron, Quateron, and Quinteron are not so precisely noted as they are elsewhere in the Caribbean (260-61).

By the end of the eighteenth century, Long’s expedient system of ranking had begun to be translated into the discourse of empirical science in the work of Charles White and others, who eventually gave it the name of “polygenesis,” or the separate creation of the different races. By the mid-nineteenth century, polygenesis and the concept of a graded “chain” or “scale” of being had become conventional concepts in British racial thinking.

After having lived in Jamaica for twelve years, Long retired in 1769 to Britain as a wealthy and respected member of British society, living there until his death in 1813.

Following the last section printed here is Chapter V, Section 1, “An Abstract of the Jamaica Code Noir, or Laws affecting Negroe and other Slaves in that Island.—And, first, of PENAL CLAUSES,” a list of regulations and prescribed punishments ranging from “moderate whipping” to death.

The History of Jamaica

Vol. II, Book II, Ch. XIII, “Of the Inhabitants”

The planters of this island have been very unjustly stigmatized with an accusation of treating their Negroes with barbarity. Some alledge, that these slave-holders (as they are pleased to call them, in contempt) are lawless bashaws, West-India tyrants, inhuman oppressors, bloody inquisitors, and a long, &c. of such pretty names. The planter, in reply to these bitter invectives, will think it sufficient to urge, in the first place, that he did not make them slaves, but succeeded to the inheritance of their services in the same manner as an English squire succeeds to the estate of his ancestors; and that, as to his Africans, he buys their services from those who have all along pretended a very good right to sell; that it cannot be for his interest to treat his Negroes in the manner represented; but that it is so to use them well, and preserve their vigour and existence as long as he is able. The antagonists, though willing to allow that he is self-interested in all he does, can hardly admit this plea; although it is evident, that the more mercenary a planter's disposition is, the stronger must the obligation grow upon him to treat his labourers well, since his own profit, which he is supposed alone to consult, must necessarily prompt him to it. In proving him therefore to be such a mercenary wretch, they effectually confute the charge of cruel usage; since the one is utterly incompatible with the other. (267)

I will assert, in my turn, and I hope without inconsistency or untruth, that there are no men, nor orders of men, in Great-Britain, possessed of more disinterested charity, philanthropy, and clemency, than the Creole gentlemen of this island. I have never known, and rarely heard, of any cruelty either practised or tolerated by them over their Negroes. If cruelties are practised, they happen without their knowledge or consent. Some few of their British overseers have given proofs of a savage disposition; but instances are not wanting to shew, that, upon just complaint and in formation of inhuman usage, the planters have punished the actor as far they were able, by turning him out of their employ, and frequently refusing a certificate that might introduce him into any other person’s. These barbarians are imported from among the liberty-loving inhabitants of Britain and Ireland. Let the reproach then fall on the guilty, and not on the planter. He is to thank his mother-country for disgorging upon him such wretches as some times undertake the management of West-India properties; and, by wanton torture inflicted on the slaves confided to their charge (the result of their own unprincipled hearts and abominable tempers), bring an unmerited censure on the gentlemen proprietors, who are no further culpable than in too often giving this employment to the outcasts of society, because, it may happen, they can get none better.

America has long been made the very common sewer and dung-yard to Britain. Is it not therefore rather ungenerous and unmanly; that the planter would be vilified, by British men, for the crimes and execrable misdeeds of British refugees! It is hard upon him to suffer this two-fold injury, first by the waste of his fortune in the hands of a worthless servant, and next by such unfair imputations upon his character. There is, I allow, no country existing without some inhuman miscreants to dishonour it. England gives birth to such, as well as other states; but I would not, from this reason, argue that every Englishman is (according to Voltaire) a savage.

The planters do not want to be told, that their Negroes are human creatures. If they believe them to be of human kind, they cannot regard them (which Mr. Sharpe insists they do) as no better than dogs or horses. But how many poor wretches, even in England, are treated with far less care and humanity than these brute animals! I could wish the planters had not too much reason on their side to retort the obloquy, and charge multitudes in that kingdom with neglecting the just respect which they owe to their own species, when they suffer many around them to be persecuted with unrelenting tyranny in various shapes, and others to perish in gaols, for want of common necessaries; whilst no expence is thought too great to bestow on the well-being of their dogs and horses. But, to have done with these odious comparisons, I shall only add, that a planter smiles with disdain to hear himself calumniated for tyrannical behaviour to his Negroes. He would wish the defamer might be present, to observe with what freedom and confidence they address him; not with the abject prostration of real slaves, but as their common friend and father. His authority over them is like that of an antient patriarch: conciliating affection by the mildness of its exertion, and claiming respect by the justice and propriety of its decisions and discipline, it attracts the love of the honest and good; while it awes the worthless into reformation. Amongst three or four hundred Blacks, there must be some who are not to be reclaimed from a savage, intractable humour, and acts of violence, without the coercion of punishment. So, among the whole body of planters, some may be found of naturally austere and inhuman tempers. Yet they, who act up to the dignity of man, ought not to be confounded with others, whose odious depravity of heart has degraded them beneath the rank of human beings. To cast general reflections on any body of men is certainly illiberal; but much more so, when applied to those, who, if their conduct and characters were fully known to the world, would appear so little to deserve them. (269-71)

Long begins his third volume with a chapter on “Negroes,” beginning with a discussion of the Negroes found in “Guiney, or Negro-land,” from where many of the slaves in Jamaica had been taken. He begins by taking up a commonly discussed question, undertaking a learned disquisition Greek and Roman practices of slavery, and on the source of the blackness of skin, with explorations of the role of the “reticular membrane,” bile, the theories of Buffon and other authorities. He then lists the obvious differences: dark skin; woolly hair (“A covering of wool, like the bestial fleece, instead of hair”); facial features including round eyes, tumid nostrils, flat noses, thick lips, and large female nipples; the “black colour of the lice which infest their bodies”; and “their bestial or fetid smell,” with Angolans smelling the worst, as well as being “the most stupid of the Negro race.” Long then lists the distinctive Negro “faculties of the mind,” under which category “we are to observe, that they remain at this time in the same rude situation in which they were found two thousand years ago.” This is followed by the selection printed below, which was reprinted in Columbian Magazine in early 1788 with the title “Observations on the Gradation in the Scale of Being between the Human and Brute Creation. Including Some Curious Particulars Respecting Negroes.”

In general, they are void of genius, and seem almost incapable of making any progress in civility or science. They have no plan or system of morality among them. Their barbarity to their children debases their nature even below that of brutes. Their barbarity to their children debases their nature even below that of brutes. They have no moral sensations; no taste but for women; gormondizing, and drinking to excess; no wish but to be idle. Their children, from their tenderest years, are suffered to deliver themselves up to all that nature suggests to them. Their houses are miserable cabbins. They conceive no pleasure from the most beautiful parts of their country, preferring the more sterile. Their roads, as they call them, are mere sheep-paths, twice as long as they need be, and almost impassable. Their country in most parts is one continued wilderness, beset with briars and thorns. They use neither carriages, nor beasts of burthen. They are represented by all authors as the vilest of the human kind, to which they have little more pretension of resemblance than what arises from their exterior form.

In so vast a continent as that of Afric, and in so great a variety of climates and provinces, we might expect to find a proportionable diversity among the inhabitants, in regard to their qualifications of body and mind; strength, agility, industry, and dexterity, on the one hand; ingenuity, learning, arts, and sciences, on the other. But, on the contrary, a general uniformity runs through all these various regions of people; so that, if any difference be found, it is only in degrees of the same qualities and, what is more strange, those of the worst kind; it being a common known proverb, that all people on the globe have some good as well as ill qualities, except the Africans. Whatever great personages this country might anciently have produced, and concerning whom we have no information, they are now every where degenerated into a brutish, ignorant, idle, crafty, treacherous, bloody, thievish, mistrustful, and superstitious people, even in those states where we might expect to find them more polished, humane, docile, and industrious. It is doubtful, whether we ought to ascribe any superior qualities to the more ancient Africans; for we find them represented by the Greek and Roman authors under the most odious and despicable character; as proud, lazy, deceitful, thievish, addicted to all kinds of lust, and ready to promote them in others, incestuous, savage, cruel, and vindictive, devourers of human flesh, and quarters of human blood, inconstant, base, and cowardly, devoted to all sorts of superstition; and, in short, to every vice that came in their way, or within their reach.

For the honour of human nature it were to be wished, that these descriptions could with justice be accused of exaggeration; but, in respect to the modern Africans, we find the charge corroborated, and supported by a consistent testimony of so many men of different nations, who have visited the coast, that it is difficult to believe they have all been guilty of misrepresenting these people; more especially, as they, tally exactly with the character of the Africans that are brought into our plantations. This brutality somewhat diminishes, when they are imported young, after they become habituated to cloathing and a regular discipline of life; but many are never reclaimed, and continue savages, in every sense of the word, to their latest period. We find them marked with the same bestial manners, stupidity, and vices, which debase their brethren on the continent, who seem to be distinguished from the rest of mankind, not in person only but in possessing, in abstract, every species of inherent turpitude that is to be found dispersed at large among the rest of the human creation, with scarce a single virtue to extenuate this shade of character, differing in this particular from all other men; for, in other countries, the most abandoned villain we ever heard of has rarely, if ever been, known unportioned with some one good quality at least, in his composition. . . .

The Negroes seem to conform nearest in character to the Ægyptians, in whose government, says the learned Goguet, there reigned a multitude of abuses, and essential defects, authorized by the laws, and by their fundamental principles. As to their customs and manners, indecency and debauchery were carried to the most extravagant height, in all their public feasts, and religious ceremonies; neither was their morality pure. It offended against the first rules of rectitude and probity; they lay under the highest censure for covetousness, perfidy, cunning, and roguery. They were a people without taste, without genius, or discernment; who had only ideas of grandeur, ill understood: knavish, crafty, soft, lazy, cowardly, and servile, superstitious in excess, and extravagantly besotted with an absurd and monstrous theology; without any skill in eloquence, poetry, music, architecture, sculpture, or painting, navigation, commerce, or the art military. Their intellect rising to but a very confused notion, and imperfect idea, of the general objects of human knowledge. But he allows, that they invented some arts, and some sciences; that they had some little knowledge of astronomy, geography, and the mathematics; that they had some few good civil laws and political constitutions; were industrious enough adepts in judicial astrology; though their skill in sculpture, and, architecture, rose not above a flat mediocrity. In these acquisitions, however imperfect, they appear far superior to the Negroes, who, perhaps, in their turn, as far transcend the Ægyptians in the superlative perfection of their worst qualities.

When we reflect on the nature of these men, and their dissimilarity to the rest of mankind, must we not conclude, that they are a different species of the same genus? (353-56)

Long then turns to the oran-outang as described by Buffon and others as an instance of a highly developed primate that approaches the human, as, he implies, the Hottentot approaches the primate.

Father Jarrie speaks of them in the same terms; and the testimony of Schoutten agrees with Pyrard on the subject of the education of these animals; he says, they are taken with nets, that they walk erect, and can use their feet occasionally as hands, in performing certain domestic services, as rinseing of glasses, presenting them to drink, turning spits, and the like. These and other examples are quoted by Mr. Buffon, who considers these animals, spoken of by voyagers under different appellations, to be only varieties of the oran-outang; and in this light be mentions the jocko, which he saw publickly shewn at Paris. This animal always walked in an erect posture; his carriage was rather awkward, his air dejected, his pace grave, and movements sedate; he had nothing of the. impatience, caprice, and mischief of the baboon, nor extravagancies of the monkey; he was ever ready and quick of apprehension; a sign or a word was sufficient to make him do what the baboon and others would not without the compulsion of the cudgel or whip. He presented his hand to re-conduct the persons who came to visit him, and stalked with a stately gait before them. He sat at table, unfolded his napkin, wiped his lips, helped himself, and conveyed the victuals to his mouth with the spoon and fork; poured the drink into a glass, brought the tea-things to the table, put in the sugar, poured out the tea, let it stand till it was cool enough for drinking, and all this with no other instigation than a sign or word from his master, and often of his own free accord; he was of a courteous, tender disposition; he spent the summer at Paris, and died the following winter at London, of a cough and consumption. He ate of every food indifferently, except that he seemed to prefer confectionary, ripe and dried fruits, and drank wine in moderation. . . .

The Indians are therefore excusable for associating him with the human race, under the appellation of oran-outang, or wild man, since he resembles man much more than he does the ape, or any other animal. All the parts of his head, limbs, and body, external and internal, are so perfectly like the human, that we cannot (says he) collate them together, without being amazed at a conformation so parallel, and an organization so exactly the same, although not resulting to the same effects. The tongue, for example, and all the organs of speech are the same in both, and yet the oran-outang does not speak; the brain is absolutely the same in texture, disposition, and proportion, and yet he does not think; an evident proof this, that mere matter alone, though perfectly organized, cannot produce thought, nor speech, the index of thought, unless it be animated with a superior principle.

His imitation and mimickry of human gestures and movements, which come so near in semblance to the result of thought, set him at a great distance from brute animals, and in a close affinity to man. If the essence of his nature consists entirely in the form and organization of the body, he comes nearer to man than any other creature, and may be placed in the second class of animal beings.

If he is a creature sui generis, he fills up the space between mankind and the ape, as this and the monkey tribe supply the interval that is between the oran-outang and quadrupeds.

When we compare the accounts of this race, so far as they appear credible, and to be relied on, we must, to form a candid judgement, be of opinion that Mr. Buffon has been rather too precipitate in some of his conclusions.

We observe that, in their native countries, they are not thoroughly known; they live sequestered in deep woods, possess great strength and agility of body, with probably sufficient cunning to guard against, as well as nimbleness to elude, surprizes. The Negroes and Indians believe them to be savage men; it is no wonder that, for the most part, they are fearful of approaching the haunts of this race; and that from some or other of these causes, none have been obtained for inspection in Europe, except very young ones, who could not escape their pursuers.

So far as they are hitherto discovered to Europeans, it appears that they herd in a kind of society together, and build huts suitable to their climate; that, when tamed and properly instructed, they have been brought to perform a variety of menial domestic services; that they conceive a passion for the Negroe women, and hence must be supposed to covet their embraces from a natural impulse of desire, such as inclines one animal towards another of the same species, or which has a conformity in the organs of generation.

The young ones exhibited in Europe have shown a quickness of apprehension, and facility of imitation, that we should admire very much in children of the same tender age.

The conformation of their limbs denotes beyond all controversy, that they are destined to an erect position of body, and to move like men. The structure of their teeth, their organs of secretion, digestion, &c. all the fame as the human, prove them entitled to subsist on the same aliments as man. The organs of generation being alike, they propagate their species, and their females suckle their young, in the same manner.

Their disposition shows a great degree of social feeling; they seem to have a sense of shame, and a share of sensibility, as may be inferred from the preceding relations; nay, some trace of reason appears in that young one, which (according to Le Brosse) made signs expressive of his idea that “bleeding in the arm had been remedial to “his disorder.” Nor must we omit the expression of their grief by shedding tears, and other passions, by modes entirely resembling the human. Ludicrous as the opinion may seem, I do not think that an oran-outang husband would be any dishonour to an Hottentot female; for what are these Hottentots?—They are, say the most credible writers, a people certainly very stupid, and very brutal. In many respects they are more like beasts than men; their complexion is dark, they are short and thick-set; their noses flat, like those of a Dutch dog; their lips very thick and big; their teeth exceedingly white, but very long, and ill set, some of them sticking out of their mouths like boars tusks; their hair black, and curled like wool; they are very nimble, and run with a speed that is almost incredible; they are very disagreeable in their persons, and, in short, taking all things together, one of the meanest nations on the face of the earth. (361-64)

. . . it is certain, that the oran-outang, though endued with brains and organs of a structure not to be distinguished from those of man by the ablest anatomists, still remains very far inferior to our idea of a perfect human being, unless he also is endowed with the faculties of reason and perception, adapted to direct him in the application of that mechanism to the same uses as we find it applied in a rational man. According to Mr. Buffon, he has eyes, but sees not; ears has he, but hears not; he has a tongue, and the human organs of speech, but speaks not; he has the human brain, but does not think; forms no comparisons, draws no conclusions, makes no reflections, and is determined, like brute animals, by a positive limited instinct. . . . When we come to view the structure of the oran-outang, we are forced to acknowledge, that his actions and movements would not be natural, unless they resembled those of man. To find him therefore excelling the brute animals in the dexterity of his manœuvres, and aptness of his imitations, does not excite our admiration, so much as the readiness of apprehension, with which, in his state of impuberty or childhood (if I may so express myself), his performances before such a variety of spectators were usually accompanied. How far an oran-outang might be brought to give utterance to those European words (the signification of whose sounds, it is plain from Buffon, and others, he has capacity to understand, so as to conform his demeanour and movements to them voluntarily at the immature period of life, when his mental faculties are in their weakest state), remains for experiment. If the trial were to be impartially made, he ought to pass regularly from his horn-book, through the regular steps of pupilage, to the school, and university, till the usual modes of culture are exhausted upon him. If he should be trained up in this manner from childhood (or that early part of existence in which alone he has been noticed by the learned in Europe), to the age of 20 or 25, under fit preceptors, it might then with certainty be determined, whether his tongue is incapable of articulating human languages. But if, in that advanced age, and after a regular process of education, he should still be found to labour under this impediment, the phænomenon would be truly astonishing; for if it be alledged, that he could not produce such sounds for want of the sentient or thinking principle to excite the organs of speech to such an effect, still we should expect him capable of uttering sounds resembling the human, just as well as a natural idiot, or a parrot, can produce them without the agency of thought. For my own part, I conceive that probability favours the opinion, that human organs were not given him for nothing: that this race have some language by which their meaning is communicated; whether it resembles the gabbling of turkies like that of the Hottentots, or the hissing of serpents, is of very little consequence, so long as it is intelligible among themselves: nor, for what hitherto appears, do they seem at all inferior in the intellectual faculties to many of the Negroe race; with some of whom, it is credible that they have the most intimate connexion and consanguinity. The amorous intercourse between them may be frequent; the Negroes themselves bear testimony that such intercourses actually happen; and it is certain, that both races agree perfectly well in lasciviousness of disposition.

But if we admit with Mr. Buffon, that with all this analogy of organization, the oran-outang's brain is a senseless icon of the human; that it is meer matter, unanimated with a thinking principle, in any, or at least in a very minute and imperfect degree, we must then infer the strongest conclusion to establish our belief of a natural diversity of the human intellect, in general, ab origine; an oran-outang, in this case, is a human being, quoad his form and organs; but of an inferior species, quoad his intellect; he has in form a much nearer resemblance to the Negroe race, than the latter bear to white men; the supposition then is well founded, that the brain, and intellectual organs, so far as they are dependent upon meer matter, though similar in texture and modification to those of other men, may in some of the Negroe race be so constituted, as not to result to the same effects; for we cannot but allow, that the Deity might, if it was his pleasure, diversify his works in this manner, and either withhold the superior principle entirely, or in part only, or infuse it into the different classes and races of human creatures, in such portions, as to form the same gradual climax towards perfection in this human system, which is so evidently designed in every other.

If such has been the intention of the Almighty, we are then perhaps to regard the oran-outang as,

“— the lag of human kind,

“Nearest to brutes, by God design'd.”

The Negroe race (consisting of varieties) will then appear rising progressively in the scale of intellect, the further they mount above the oran-outang and brute creation. The system of man will seem more consistent, and the measure of it more compleat, and analagous to the harmony and order that are visible in every other line of the world's stupendous fabric. . . . The species of every other genus have their certain mark and distinction, their varieties, and subordinate classes: and why should the race of mankind be singularly indiscriminate? (369-72)

The examples which have been given of Negroes born and trained up in other climates, detract not from that general idea of narrow, humble intellect, which we affix to the inhabitants of Guiney. We have seen learned horses, learned and even talking dogs, in England; who, by dint of much pains and tuition, were brought to exhibit the signs of a capacity far exceeding what is ordinarily allowed to be possessed by these animals. The experiment has not been fully tried with the oran-outangs; yet, from what has hitherto been proved, this race of beings may, for aught we know to the contrary, possess a share of intellect, which, by due cultivation, might raise them to a nearer apparent equality with the human, and make them even excel the inhabitants of Quaqua, Angola, and Whidah. Mr. Hume presumes, from his observations upon the native Africans, to conclude, that they are inferior to the rest of the species, and utterly incapable of all the higher attainments of the human mind. Mr. Beattie, upon the principle of philanthropy, combats this opinion; but he is unfortunate in producing no demonstration to prove, that it is either lightly taken up, or inconsistent with experience. He likewise makes no scruple to confound the Negroes and Mexican Indians together, and to deduce conclusions from the ingenuity of the latter, to shew the probable ingenuity of the former. We might reasonably suppose, that the commerce maintained with the Europeans for above two centuries, and the great variety of fabrics and things manufactured, which have been introduced among the Guiney Negroes for such a length of time, might have wrought some effect towards polishing their manners, and exciting in them at least a degree of imitative industry; but it is really astonishing to find, that these causes have not operated to their civilization; they are at this day, if any credit can be given to the most modern accounts, but little divested of their primitive brutality; we cannot pronounce them insusceptible of civilization, since even apes have been taught to eat, drink, repose, and dress, like men; but of all the human species hitherto discovered, their natural baseness of mind seems to afford least hope of their being (except by miraculous interposition of the divine Providence) so far refined as to think, as well as act like perfect men. (375-77)

In the fourth chapter of Book 3, Long seeks to prove the inferiority of the Negro by citing a poem (written in Latin) by Francis Williams of Jamaica that, judged by the highest standards, Long finds wanting in beauty, grace, and sophistication.. The chapter concludes with this passage, an explicit allusion to the Chain of Being.

The Spaniards have a proverbial saying, “Aunque Négros somos génte”; “though we are Blacks, we are men.” The truth of which no one will dispute; but if we allow the system of created beings to be perfect and consistent, and that this perfection arises from an exact scale of gradation, from the lowest to the highest, combining and connecting every part into a regular and beautiful harmony, reasoning them from the visible plan and operation of infinite wisdom in respect to the human race, as well as every other series in the scale, we must, I think, conclude, that,

The general order, since the whole began,

Is kept in nature, and is kept in man.

Order is heaven's first law; and, this confest,

Some are, and must be, greater than the rest. (484-85)

Vincent Brown, Tacky’s Revolt: The Story of an Atlantic Slave War (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2020).

Howard Johnson, “Edward Long, Historian of Jamaica,” Edward Long, The History of Jamaica; Reflections on its Situations, Settlements, Inhabitants, Climate, Products, Commerce, Laws, and Government (Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 2002), i-xxv.

Suman Seth, “Materialism, Slavery, and The History of Jamaica,” Isis 105 (Dec. 2014) 4: 764-72.